|

Landscapes of the

Central Great Plains

Chapter III

Arkansas River and

Platte River Lowlands

James S. Aber and Susan W. Aber

Emporia State University Emeritus

|

III.1 Introduction

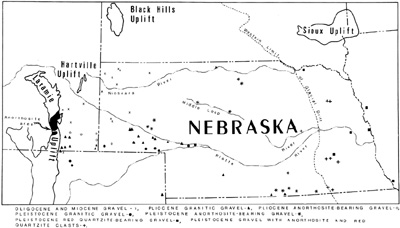

The Arkansas River and Platte River are the principal Rocky Mountain drainage systems that descend eastward across the central Great Plains. They arise at the continental divide, pass through the Front Range, and flow into the Missouri and Mississippi rivers to the east. In some segments, these rivers follow sinuous courses, for example the Platte River valley across south-central Nebraska, which suggests little influence of bedrock or other processes on stream flow. In eastern Nebraska, however, the Platte River was displaced by glaciation. In other portions, the rivers are relatively straight for long distances, then bend abruptly in a different direction, as demonstrated by the Arkansas River valley in southwestern Kansas. This pattern is an indication for structural control by underlying bedrock.

Both river systems are essentially remnants of former drainages that transported enomous volumes of sand and gravel from the Rocky Mountains, particularly during the Oligocene, Miocene, and Pliocene epoches, and built up the High Plains. Since then, the rivers have alternated between erosion of valleys and deposition of alluvium. The rivers have shifted back and forth over extensive alluvial plains, and, in places, wind has blown dunes into sand hills terrain.

| Diversion of water from Cucharas Creek in a small ditch (left) for spring flood irrigation of hay in montane valleys (right). Tributary of the Arkansas River near La Veta, Colorado.

|

|

| Overview of Lake Pueblo and Pueblo Dam on the Arkansas River, just west of Pueblo, Colorado. Part of a fish hatchery is visible to right. Canal across the bottom of scene is supplied by Lake Pueblo and is operated by the Bessemer Irrigating Ditch Co. Kite aerial photograph.

|

Both rivers are altered heavily by human activities, namely extraction of water for irrigation, industry, urban use, and recreation. This begins in small tributaries in montane valleys, and continues downstream in large reservoirs. This water resource has been essential for urban growth along the Front Range corridor and sustains irrigated agriculture across the High Plains. In southeastern Colorado, for instance, water is withdrawn from the Arkansas River to support irrigated agriculture. Water is diverted via canals directly to irrigated fields as well as into holding reservoirs in tributary valleys, from whence the water is further distributed to agricultural fields.

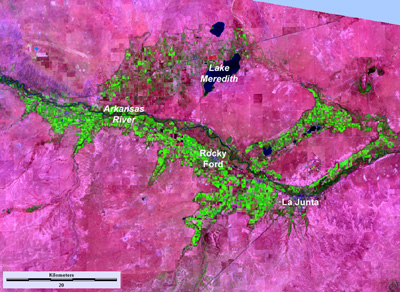

| False-color satellite image of the Arkansas River valley in the Rocky Ford-La Junta vicinity, southeastern Colorado. Bright green indicates irrigated crops; maroon-pink shows dry upland areas. Lake Meredith is a major storage point for water diverted from the Arkansas River. Landsat TM; August 7, 2009.

| |

| View over the eastern portion of Lake Meredith with Sugar City in the left background. This is a storage reservoir for irrigation water distributed downstream in the Rocky Ford vicinity. Note the well-developed wetland vegetation in the foreground. Helium-blimp airphoto.

|

Return to beginning.

Return to beginning.

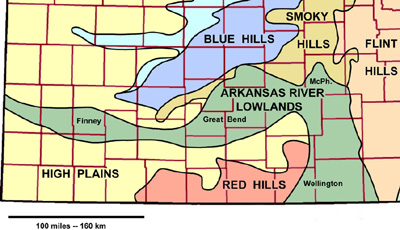

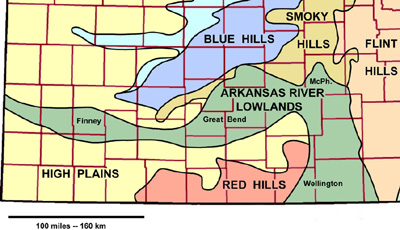

III.2 Arkansas River Lowlands

The Arkansas River courses through southwestern and south-central Kansas. The adjacent lowlands ranges from a few miles wide on the Colorado border to scores of miles across at the Oklahoma border. The province may be divided, from west to east, into Finney, Great Bend, McPherson, and Wellington sectors, which are combined for purposes of this discussion. The lowlands borders several other landscape regions including the High Plains, Smoky Hills, Blue Hills, Flint Hills and Red Hills. Terraces, old stream channels, and sand hills locally give some topographic relief to an otherwise flat landscape within the lowlands.

| Detail of the sectors within the Arkansas River Lowlands: Finney, Great Bend, McPherson (McPh.), and Wellington. Adapted from Aber and Aber (2009).

| |

| Arkansas River (left) looking downstream near Coolidge in westernmost Kansas. Frontier Ditch (right) at Coolidge, the first irrigation ditch to enter Kansas near the Colorado border.

|

|

In most places, the Arkansas River Lowlands is situated below adjacent upland regions. However, the northeastern portion is actually higher in elevation than the Smoky Hills and Flint Hills, where the McPherson Lowland sector forms a north- and east-facing escarpment in McPherson and Marion counties. This is a good example of inversion of topography, in which what was the lowest topographic feature is now the highest. Most portions of the Arkansas River Lowlands are underlain by stream-deposited sand and gravel of Quaternary age.

In some portions, this sandy sediment has been blown into dunes, particularly along the southern margin of the Arkansas River. Most of the dunes are stabilized by sand-sage prairie vegetation, but active dunes are present near Syracuse in Hamilton County. The Great Bend sector contains one of the largest sand-dune terrains in the United States, covering parts of Barton, Stafford, Pawnee, Edwards, Kiowa, Pratt, Rice and Reno counties (Muilenburg 1961). The Wellington Lowland sector, in contrast, is an eroded surface on Permian shale with little alluvial sediment cover.

| Syracuse Sand Dunes Park (left) immediately south of the Arkansas River in Hamilton County. Dune-buggy trails criss-cross Holocene sand hills. Sand hills stablized by vegetation at Camp Aldrich (right) near Claflin, Barton County. Kite aerial photograph by ESU students.

|

|

| View toward the northwest over the Ninnescah River in the Wellington Lowland sector of the Arkansas River Lowlands, Sedgwick County, Kansas. The former biological field station of Wichita State University is visible on the river bank in lower left corner. Green winter wheat fields are evident in the background of this spring view.

|

The Arkansas River displays a distinctive route across the state of Kansas. From the Colorado border, it flows generally toward the east-southeast to near Dodge City, where it turns abruptly toward the northeast. At Great Bend, the river turns again eastward and curves toward the southeast and south for the remainder of its path across south-central Kansas. The Great Bend Lowland sector is unusually wide, south of the river, which suggests the Arkansas River has migrated northward a considerable distance during its evolution, as postulated by Haworth (1897).

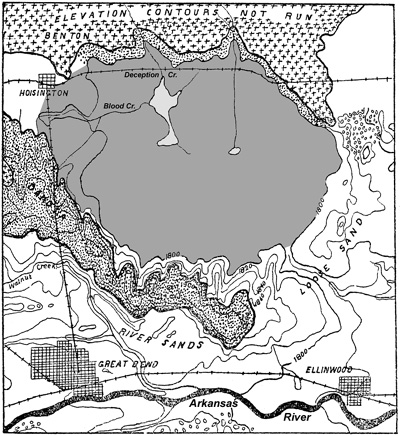

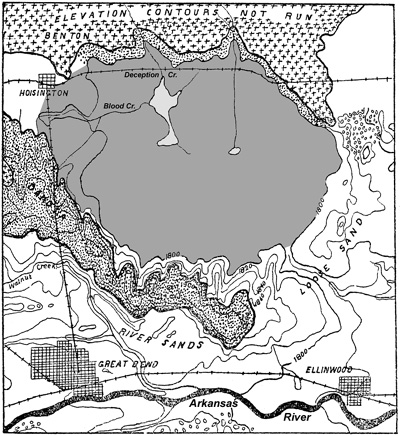

At the northernmost edge of the Great Bend Lowland, Cheyenne Bottoms is a large natural depression that is the terminal point of an enclosed drainage basin in Barton County. The "bottoms" covers about 64 square miles (166 km2) and has a flat floor with elevation around 1800 feet (550 m), which is 20-40 feet lower than the Arkansas River valley at Great Bend. Cheyenne Bottoms is famous for great flocks of migrating waterfowl and shorebirds that include many rare and endangered species (Penner 2010). It is considered by many to be the single most important wetland site for migrating birds in North America (Zimmerman 1990). Surface water and vegetation vary substantially from year to year, depending on drought and flood cycles (Aber et al. 2021).

| Sketch map of Cheyenne Bottoms (shaded gray) near Great Bend, Barton County, Kansas. Adapted from Haworth (1897).

| |

| Autumn overviews of the Nature Conservancy marsh at Cheyenne Bottoms. Drought status with dry pools (left). Tracks in dry mud flats were made by local youth riding ATVs. Wet phase following repeated rains and floods (right). Pools are full of water and wetland vegetation has recovered. Looking toward the northwest with Hoisington in the background; kite aerial photographs.

|

|

The basin is developed in Cretaceous bedrock overlying upper Permian salt-bearing strata. The cause of sinking at Cheyenne Bottoms is likely due to Pleistocene fault movement that allowed groundwater to penetrate deeply and partly dissolve the Hutchinson Salt approximately 1000 feet (300 m) below the surface (Bayne 1977). As salt was dissolved along faults, adjacent salt squeezed in from the surroundings, which led eventually to subsidence of the surface basin (Keiswetter et al. 1995).

The faults are perhaps an expression of the intersection of regional fault trends or an ancient meteorite impact structure in the Proterzoic basement about 4000 feet deep (Merriam 2011). Cheyenne Bottoms appears to be the focal point for regional crustal tilting in central Kansas, as evidenced by northward migration of the Arkansas River and the anomalous bend of the river in this vicinity.

Another famous wetland, Quivira National Wildlife Refuge, is located to the south in Stafford County in the Great Bend Lowland sector. Rattlesnake Creek feeds a series of saline marshes. The salt is derived from subsurface solution of upper Permian bedrock. Groundwater transports the salt toward the surface, where it emerges in saline springs that feed streams. As the water moves through the marshes, evaporation leads to increased salinity of seawater character. Similar high-salinity groundwater is found along the upper Ninnescah River and lower Arkansas River valleys (Buddemeier et al. 1995). Underground salt mining at Hutchinson has a long history and continues to be an important part of the local economy.

| View to the northwest over Little Salt Marsh at Quivira National Wildlife Refuge. A levee and drainage structures are used to control water level; Rattlesnake Creek exits the marsh to upper right and flows into Big Salt Marsh a few miles to the north. Kite aerial photograph.

|

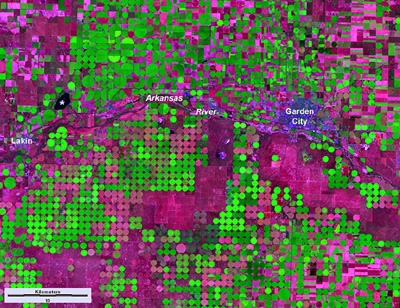

The Arkansas River provided water for early settlement and agricultural development, and several cities grew up along its banks. In the late nineteenth century, the supply of water was considered unlimited, and numerous canal-and-ditch systems were constructed to divert water from the river for irrigation of adjacent farmland in the Finney Lowland sector (see above). Some of these systems are still in operation today, namely in the vicinity of Lakin and Garden City.

| Satellite image of the Arkansas River valley in the Lakin-Garden City vicinity, southwestern Kansas. Bright green indicates irrigated crops; maroon-pink shows dry-fallow areas. Small irrigation circles are one-half mile (0.8 km) in diameter; large circles are one mile (1.6 km) in diameter. Asterisk (*) indicates Lake McKinney, a holding point for water diverted from the Arkansas River. Landsat TM; August 4, 2007.

| |

| Lake McKinney (left) in the right foreground, road along dam to left, and Lakin in the distant background. Kite airphoto. The man-made reservoir is a storage point for water diverted from the Arkansas River west of Lakin via the Amazon Ditch (right). From Lake McKinney, water is transported via the Great Eastern Ditch into the area northwest of Garden City.

|

|

The risk of flooding is slight in western Kansas, but increases in the central portion of the state, as happened at Great Bend (2006) and Hutchinson (2007). Most of the Arkansas River Lowlands, except for the Wellington Lowland sector, is part of the

Steep bluffs and escarpments border several sections of the valley, particularly along the North Platte River which is deeply entrenched below the High Plains upland. Well-known landmarks include Chimney Rock and Scotts Bluff, both created by erosion of Miocene and Oligocene strata along the valley sides. Resistant Arikaree (Miocene) sandstone caps the bluffs, buttes, and pinnacles as well as Wildcat Ridge between the North Platte River and Pumpkin Creek valleys (Pabian and Swinehart 1979). Scotts Bluff stands more than 750 feet (>225 m) above the North Platte River valley.

Return to beginning.

Return to beginning.

Return to beginning.

Return to beginning.

Return to beginning.

Return to beginning. Combined references.

Combined references.