STRUCTURAL GEOLOGY EXERCISES

with Glaciotectonic Examples – Part III

James S. Aber, Professor Emeritus

Emporia State University, Kansas

7. EQUAL-AREA STEREONET I

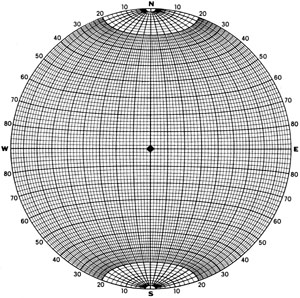

Schmidt stereonet

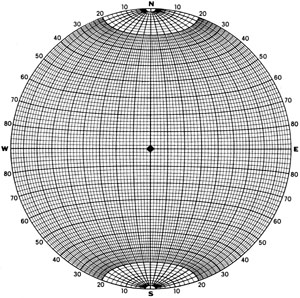

The equal-area or Schmidt stereonet is a different stereographic projection on which size is preserved, but angles and shapes are distorted—see Fig. 7-1. Each quadrangle on the stereonet is equal in size or area, whereas shape of quadrangles varies from almost square near the center to narrow, curved rectangles near the edge. Unlike the Wulff stereonet, on which meridians and parallels are circular arcs, the meridians and parallels of the Schmidt stereonet are oval curves.

| Figure 7-1. Schmidt stereographic projection. Print out a full-sized version for the problem below.

|

Plotting of lines and planes on the Schmidt stereonet is carried out following exactly the same procedures as used on the

Wulff stereonet in the previous exercise. All the operations described may be accomplished just as easily on either stereographic projection. Because it maintains size, the Schmidt stereonet is visually more pleasing than the equal-angular stereonet, and the Schmidt stereonet has proven more popular.

The Schmidt stereonet has one important advantage—it preserves area. Therefore, the density of plotted data may be analyzed. In many situations, dozens or even hundreds of measurements of linear or planar features may be made, and all the data could be plotted on a single Schmidt stereonet to display the over

all structural pattern.

Petrofabric analysis

Petrofabric refers to the size, shape, and arrangement of

grains which make up a body of rock or sediment. Size and shape

of grains vary from flat clay flakes <2 microns long, to intergrown crystals a few mm or cm long, to large rounded boulders >1

m in diameter. The grains may be arranged in a linear fabric,

called lineation, or in a planar fabric, called foliation. The

terms lineation and foliation are commonly applied to metamorphic

rocks. However, these terms may be used for any type of rock or

sediment whose fabric was primarily created by deformation. The

orientation of lineation is given by trend and plunge; foliation

is specified by strike and dip.

Petrofabric is normally related to the larger structures

formed at the same time the fabric developed. For example, lineation may parallel fold axes, or foliation may parallel fold

axial planes. The petrofabric of a rock reflects the internal

changes or strain that occurred within the rock body during deformation (further discussion in exercise 9). Thus, petrofabric analysis could give important additional information for overall

structural interpretation.

Till fabric

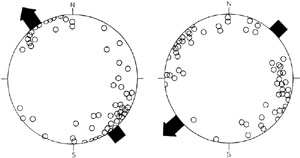

Consider, for example, till fabric, a kind of lineation. The

orientations of long axes of elongated pebbles embedded within

the till are measured to ascertain the direction of ice movement.

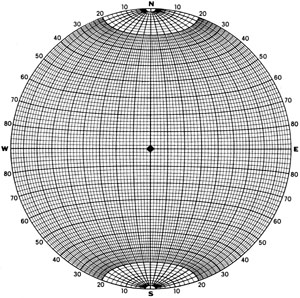

Typically 50 pebbles are measured, and all 50 axes plotted as

points on a stereonet. The data points may then be contoured to

show the pattern of data density. Another approach is to show

each pebble axis as a tiny circle on the stereonet, in an attempt

to retain the integrity of individual measurements, while giving

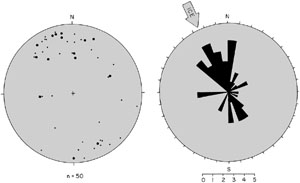

the impression of a contouring effect—see Fig. 7-2.

| Figure 7-2. Representative long-axis till-fabric plots on the Schmidt stereonet. Till fabric parallel with ice movement (left), and till fabric transverse to ice movement (right). From Nielsen and Houmark-Nielsen (1983, figs. 218 and 220).

|

The most common till fabric is parallel to ice movement with

a majority of pebbles plunging at a slight angle in the upice

direction. Fewer pebbles plunge slightly down ice, and still fewer pebbles may lie approximately transverse to

ice flow. The transverse till fabric is more rare, but still appears often enough to warrant discussion. In this

type, pebble axes are about equally divided, lying near-horizontal or plunging slightly left or right, perpendicular to ice

flow. Mixed or ambiguous till fabrics also occur, but are of

limited use for establishing ice movement direction.

| Till exposed in a drumlin at Galway, Ireland. Overview (left) and close-up shot (right). A classic example of boulder-clay in which pebbles and cobbles of limestone appear to float in a fine-grained matrix. Long axes of larger clasts could be used to determine the till fabric.

|

|

A well-developed till fabric is thought to reflect the

shearing action at the base of a glacier when the till was

deposited. Elongated pebbles became aligned parallel either with

the strike or dip of inconspicuous shear planes cutting through

the till. The fabric was, thus, created by subglacial deformation

penecontemporaneous with deposition of the till. Subsequent reworking of the till or a shift in ice-movement direction could alter or destroy the original fabric, however.

Problem

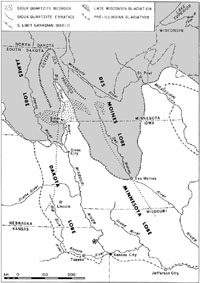

The glaciation of northeastern Kansas was the greatest Pleistocene ice-sheet coverage to ever take place on the Great Plains of North America. The maximum ice limit reached west of the Missouri River, extending across

northeastern Kansas and eastern Nebraska, far south of the younger Wisconsin glacial limit—see Fig. 7-3.

The glaciation of Kansas is marked by the Independence Formation, which includes till and stratified drift.

Age of the Independence Formation is in the range 600,000 to 720,000 years ago (Aber 1991), making it one of the oldest continental glaciations still preserved in the Pleistocene record.

| Figure 7-3. Map of northern Great Plains showing Wisconsin (gray) and Independence (pre-Illinoian) glacial features. Location of Independence Formation stratotype is indicated by asterisk. Adapted from Aber (1991).

|

The Wisconsin glaciation of the northern Great Plains consisted of two prominent ice lobes—Des Moines and James River, whose movements were controlled by bedrock topography. The lobes

advanced southward following broad troughs either side of the

Coteau des Prairies upland. The southern end of the Coteau des

Prairies is underlain by a high bedrock ridge of resistant Sioux

Quartzite, located in southwestern Minnesota and adjacent South Dakota.

The Independence glaciation likewise consisted of two ice lobes—Minnesota to the east and Dakota to the west. These two lobes were confluent over the crest of the Coteau des Prairies, but

maintained their separate identities southward to the ice margin.

The Minnesota lobe advanced southward through Iowa, into Missouri, and entered Kansas from the northeast. Conversely, the Dakota lobe came from the Dakotas, across Nebraska, and moved

into Kansas from the northwest. Evidences from glaciotectonic

structures and glacial striations confirm these two directions of

ice advance in northeastern Kansas (Dellwig and Baldwin 1965).

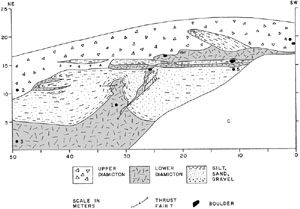

Deposits of both ice lobes are present at the Independence Formation

stratotype, near Atchison, Kansas—see Fig. 7-4. The lower

till is a gray, wood-bearing, compact till that exhibits a

large diapir and thrust faults. The diapir and thrusts extend up

into fine sand and silt beds that were deposited in an ice

marginal lake. Recumbent, isoclinal folds near the top of this

sand were created by the ice advance that laid down the overlying

upper till.

| Figure 7-4. Independence formation stratotype near Atchison, Kansas. Two tills separated by sand display a variety of ice-pushed structures. Section measured in m with no vertical exaggeration; taken from Aber (1985, fig. 4).

|

| Overview (left) of Independence Formation stratotype near Atchison, Kansas. Upper brown till (upper right) overlies deformed sand. Lower gray till (bottom left) is deformed in a diapir that intrudes sand in the middle of the section (behind ladder). Close-up view (right) of the large diapir of lower gray till.

|  |

| Planed and striated limestone boulder embedded in lower gray till near site 3 (fig. 7-4). Knitting needle points in direction of ice movement from northeast to southwest. Silva compass for scale.

|

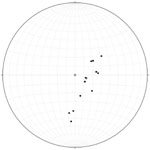

The upper till was deposited by northwesterly ice movement. Axes of subjacent isoclinal folds plunge slightly to the northeast, and striations on bevelled boulder tops trend NW-SE. Till fabric measurements at site 4 (upper right, fig. 7-4) are displayed in two formats in Figure 7-5.

| Figure 7-5. Till fabric plots for upper Independence till (site 4, fig. 7-4). Rose diagram (right); equal-area stereonet (left). Total of 50 pebble long axes are plotted on each diagram.

|

The rose diagram shows measurements grouped into 10-degree

intervals according to plunge direction, but the plunge angles

cannot be indicated. Pebble axes are plotted on the stereonet

according to pebble shape: (1) large dots = blade and roller

shapes, (2) small dots = disk and spheroid shapes. However, differences in pebble shapes do not appear to affect the orientations of pebble long axes. The fabric is clearly the parallel

type: most pebbles plunge slightly north or northwest, a smaller

group plunges gently in the opposite direction, and a few pebbles

lie in transverse positions with steeper plunge angles. Ice movement from the NNW is indicated and agrees with other directional features.

Tables 7-1 and 7-2 (below) present fabric data for sites 1 and 3 from the lower gray till in the Independence Formation stratotype (see fig. 7-4 for site locations). Forty-two measurements are given for site 1 and 50 for site 3. Use these data for the following.

- Plot all 50 measurements for site 3 on a Schmidt stereonet. Note for Stereonet 11, enter trend/plunge values for a linear data set.

- Is the till fabric at site 3 parallel, transverse, or mixed in style?

- What general direction of ice movement is indicated by the till fabric at site 3?

- Plot all measurements for site 1 on a second Schmidt stereonet. Note for Stereonet 11. Be sure to open a new linear dataset; do not add site 1 data to the site 3 dataset.

- Is the till fabric at site 1 parallel, transverse, or mixed in style?

- Is the site 1 till fabric similar to the till fabric at site 3? Describe any differences between the two fabrics.

- Thrust faults that cut the diapir and adjacent sand near site 1 have an average strike/dip = 330/40°. Plot this fault as a plane (arc) on the stereonet for site 1. Describe any relationship between the fabric pattern and fault position that you see. Note for Stereonet 11, add a planar dataset for the thrust fault to the plot for till fabric at site 1.

- Give an explanation for how the till fabric at site 1 was created.

- What direction of ice movement was responsible for depositing and deforming the lower till?

- Based on all the available information, determine which of the ice lobes deposited each of the tills at the Independence Formation stratotype.

Table 7-1. Till fabric measurements from Independence Formation stratotype—site 1.

| Trend/Plunge | Trend/Plunge | Trend/Plunge |

| 1. 250/40 | 15. 080/30 | 29. 157/27 |

| 2. 115/09 | 16. 295/32 | 30. 072/33 |

| 3. 077/00 | 17. 322/74 | 31. 220/06 |

| 4. 340/56 | 18. 295/15 | 32. 288/71 |

| 5. 335/57 | 19. 328/78 | 33. 130/46 |

| 6. 063/04 | 20. 000/90 | 34. 035/08 |

| 7. 317/36 | 21. 040/36 | 35. 270/25 |

| 8. 136/49 | 22. 298/21 | 36. 003/55 |

| 9. 015/60 | 23. 280/26 | 37. 336/24 |

| 10. 072/35 | 24. 042/70 | 38. 090/62 |

| 11. 034/61 | 25. 342/54 | 39. 257/26 |

| 12. 088/39 | 26. 048/25 | 40. 044/65 |

| 13. 135/07 | 27. 255/15 | 41. 078/34 |

| 14. 338/71 | 28. 070/56 | 42. 110/10 |

Table 7-2. Till fabric measurements from Independence Formation stratotype—site 3.

| Trend/Plunge | Trend/Plunge | Trend/Plunge |

| 1. 153/06 | 18. 071/30 | 35. 068/15 |

| 2. 153/12 | 19. 133/02 | 36. 082/26 |

| 3. 044/03 | 20. 112/23 | 37. 315/17 |

| 4. 130/08 | 21. 054/21 | 38. 053/15 |

| 5. 244/20 | 22. 074/27 | 39. 160/42 |

| 6. 085/35 | 23. 008/40 | 40. 136/19 |

| 7. 062/36 | 24. 086/01 | 41. 341/21 |

| 8. 138/20 | 25. 038/32 | 42. 150/24 |

| 9. 250/08 | 26. 009/47 | 43. 247/18 |

| 10. 272/00 | 27. 105/10 | 44. 250/11 |

| 11. 070/19 | 28. 145/25 | 45. 110/00 |

| 12. 036/20 | 29. 245/24 | 46. 070/04 |

| 13. 104/35 | 30. 082/25 | 47. 140/13 |

| 14. 186/08 | 31. 230/27 | 48. 028/25 |

| 15. 170/23 | 32. 270/15 | 49. 108/00 |

| 16. 298/30 | 33. 165/30 | 50. 080/14 |

| 17. 160/06 | 34. 110/32 |

References

- Aber, J.S. 1985. Definition and model for Kansan glaciation. Ter-Qua Symposium Series 1:53-60.

- Aber, J.S. 1991. The glaciation of northeastern Kansas. Boreas 20:297-314.

- Dellwig, L.F. and Baldwin, A.D. 1965. Ice-push deformation in northeastern Kansas. Kansas Geological Survey, Bulletin 175, part 2.

- Nielsen, P.E. and Houmark-Nielsen, M. 1983. Till fabric. in, Ehlers, J. (ed.), Glacial Deposits in North-west Europe, p. 207-209. A. A. Balkema, Rotterdam.

8. EQUAL-AREA STEREONET II

Plotting poles to planes

Plotting 50 pebble axes on the stereonet, as with till

fabric diagrams, is straightforward. Each axis is a linear

feature, and so, plots as a single point. In other situations,

though, it may be necessary to deal with a large number of planar

features. However, plotting 50 planes as arcs on the stereonet

would create visual clutter and confusion.

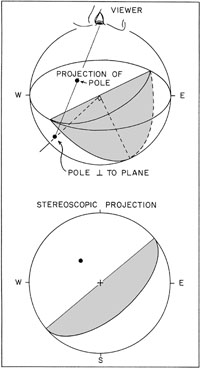

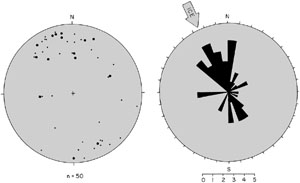

To simplify plotting planes on the stereonet, it is convenient to plot the pole to each plane. The pole is a line running

through the center of the projection sphere and perpendicular to the plane—see Fig. 8-1. The pole forms a 90° angle with the strike line and a 90° angle with the dip line. Thus, the pole is always be found in the opposite quadrant of the stereonet from the dip of the plane.

| Figure 8-1. Pole perpendicular to dipping plane in projection sphere (above), and the resulting stereographic projection of the plane and its pole (below).

|

In the example (fig. 8-1), the plane strikes/dips 50/45°. The plane's pole trends 320° (90° from strike) and

plunges 45°. Note that plane dip angle plus pole plunge angle must equal 90°. The pole for a horizontal plane plots at

the center of the stereonet, and the pole for a vertical plane plots as two "half points" on opposite edges of the stereonet. The procedure for plotting a pole to a plane is as follows.

- Mark the plane's strike and dip compass directions on the outer edge of the stereonet.

- Rotate the tracing so the strike mark points north and the dip mark falls on the E-W axis of the stereonet.

- Count the dip angle outward from the center of the stereonet along the E-W axis toward the side opposite the

dip, and mark that point.

- Rotate the tracing back to its original position. The marked point represents the pole to the plane.

With a little practice, you will soon find it is easier to plot a plane's pole than to plot the actual plane. By plotting poles, a large number of planar measurements may be placed on a Schmidt stereonet in order to display and analyze various structural patterns.

Constructing fold axes

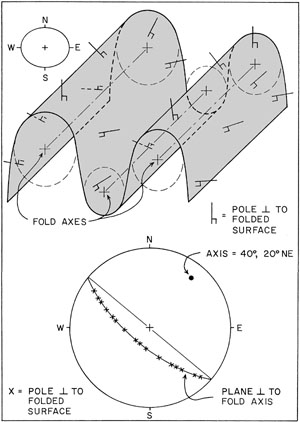

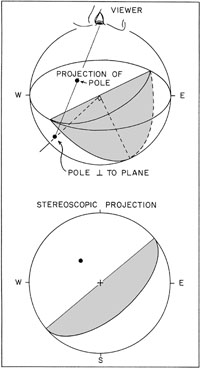

The technique of plotting poles to bedding planes is particularly useful for determining the orientation of a fold axis, where the fold axis is not directly discernible. Such a plot is called a Pi diagram, and is analyzed on the assumption that the folds are parallel or cylindrical in style (Billings 1972).

Figure 8-2 illustrates a surface folded in a cylindrical

style around three parallel fold axes. Poles perpendicular to

the folded surface are indicated in various positions. Note that

all of the poles are perpendicular to the fold axes, regardless

of their positions on the folded surface. In fact, the poles

define a plane which is perpendicular to the fold axes.

| Figure 8-2. Poles on a series of northeast-plunging cylindrical folds (above), and the stereonet plot of those poles (below). On the stereonet, the poles fall on an arc that represents a plane perpendicular to the fold axis.

|

When plotted on a Schmidt stereonet, the poles to a

cylindrical fold fall on an arc which represents the plane

perpendicular to the fold axis. This arc is found simply by

rotating the tracing until the poles line up along the same N-S

meridian of the stereonet. The arc may then be sketched onto the

tracing. As this arc is perpendicular to the fold axis, the pole

to the arc represents the so-called constructed fold axis (fig.

8-2).

Problem

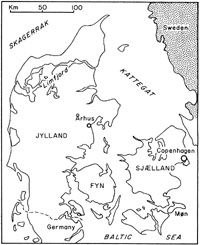

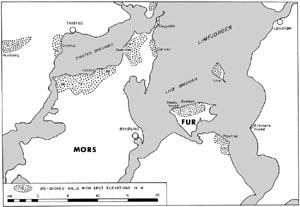

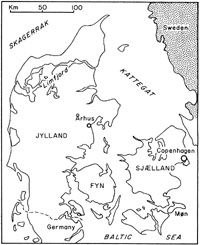

Ice-shoved terrain and structures are well developed in the Limfjord region of northern Denmark—see Figs. 8-3, 8-4. The Limfjord is a large, relatively shallow estuary around whose margins ice pushing has folded and thrust Eocene strata into prominent ridges that stand >50 m above the surrounding lowlands (Gry 1940, 1979). The disturbed Eocene strata, which are part of the Fur Formation, consist of interbedded clayey diatomite, volcanic ash, and limestone layers. This formation was especially suspectible to glaciotectonism and is deformed in all surface exposures of the region (Aber and Ber 2007).

| Figure 8-3. Denmark location map. The Limfjord estuary extends across the northern part of the Jylland pennisula. Stipling shows crystalline bedrock in Sweden.

|

| Figure 8-4. Map of the Limfjord region of northern Jylland, Denmark showing zones of deformed Eocene strata (Fur Formation) in ice-pushed hills. The highest ridges exceed 70 m in elevation. Problem site is Ertebølle Hoved on east side of map.

|

The ice shoving presumably took place during the late Pleistocene glaciation, some 13,000 to 25,000 years ago (Berthelsen 1978). All manner of glaciotectonic structures from beautifully concentric folding to overturned, thrust and contorted folding is developed in the Limfjord district. Northern Jylland was subjected to ice advances from two directions: a) Norwegian advance directly from the north coming across the Skagerrak, and b) multiple northeasterly advances moving from Sweden across the Kattegat. Each glaciation formed ice tongues moving along topographic troughs that are now parts of the Limfjord.

| Large exposure of Fur Formation in Harhøj gravel pit on the island of Mors, Limfjord estuary, northwestern Denmark. Overturned syncline (left) with a core of glacial gravel leads into a sharply folded anticline (right) and another syncline. After folding, the structure was truncated by overriding ice.

|  |

| Fegge, a peninsula at the northern end of the island of Mors in the Limfjord (see fig. 8-4). Kite aerial photo (left) and ground shot (right) showing the cliff exposure on the side of the flat-topped hill. The cliff reveals folded and thrust bodies of Fur Formation.

|

|

At Ertebølle Hoved, ice pushing created parallel folds in the Fur Formation. Table 8-1 (below) lists 14 strike-and-dip measurements from this locality. On the basis of these data, use the Schmidt stereonet to:

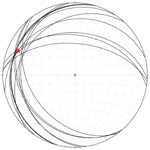

- Construct two stereonets. First plot all planes as arcs, and then plot each plane as a pole—see following examples—using either paper or Stereonet 11.

| Begin by entering the 14 strike-and-dip values for a planar dataset. The planes plot as arcs on the stereonet. Notice two sets of planes representing two fold limbs. You may visually approximate the fold axis at the point where most of the planes intersect (red asterisk). |

| Next convert the strike-and-dip values in Table 8-1 into pole values. Strike - 90 = pole trend; 90 - dip = pole plunge. For example, site 1: 279 - 90 = 189 (trend) and 90 - 44 = 46 (plunge). Enter the pole values in a new linear dataset. You should get a plot with 14 points that represent poles to planes. |

- Find the plane (arc) along which these poles approximately lie. Sketch in this arc; it is normal to the fold axis.

- Determine the trend and plunge of the pole to the plane sketched in step 2; this pole is the constructed fold axis.

- Assuming that ice movement was more-or-less perpendicular to the fold axis, what direction of ice advance is indicated by the structural data at this locality?

- Which late Pleistocene ice advance do you think deformed the Fur Formation at Ertebølle Hoved?

Table 8-1. Measurements of bedding planes from several places at Ertebølle Hoved, Denmark.

| Site | Strike/Dip | Site | Strike/Dip |

1 279/44

8 194/13

2 275/54

9 194/12

3 273/41

10 175/26

4 256/24

11 171/24

5 223/26

12 144/37

6 214/13

13 141/26

7 197/13

14 | 139/24 | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Strike and dip according to the right-hand rule.

Adapted from Gry (1940, p. 588).

References

- Aber, J.S. and Ber, A. 2007. Glaciotectonism. Developments in Quaternary Science 6, Elsevier, Amsterdam, 246 p.

- Berthelsen, A. 1978. The methodology of kineto-stratigraphy as applied to glacial geology. Geological Society of Denmark, Bulletin 27, Special Issue, p. 25-38.

- Billings, M.P. 1972. Structural Geology. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, 606 p.

- Gry, H. 1940. De istektoniske forhold i moleromraadet. Meddr. Dansk Geologisk Forening 9, p. 586-627.

- Gry, H. 1979. Beskrivelse til geologisk kort over Danmark, Kort bladet Løgstær, Kvartære aflejringer. Danmarks Geologisk Undersøgelse, I række, Nr. 26.

9. ROCK STRENGTH

Stress and strain

Geologic bodies may be deformed by application of stress or

pressure, and the resulting change in size or shape of the body

is called strain. Stress is simply force per unit area, and may

be expressed in such common units as: pounds per square inch

(psi), kg/cm², or atmospheres (1 atm. = 14.7 psi or about 1

kg/cm²) pressure.

A stress unit commonly used in structural geology is the

kilobar (kb), which is 1000 bars or approximately 1000 atmospheres. For continental rocks of medium density, a pressure of 1 kb is achieved at a depth of 3½ to 4 km (2 to 2½ miles), and a pressure of 10 kb is reached at the base of continental crust. It was under such high-pressure conditions that plutonic and metamorphic

rocks now exposed in mountain belts and shields were created.

The high pressure imposed on deeply buried rocks due to

weight of the overburden is uniform and equal in all directions.

A similar, uniform pressure is experienced by underwater divers.

Such stress in crustal rocks is called lithostatic pressure, and it is determined solely by the thickness and density of the overburden. It is compressive or positive stress, in contrast to tension which is a negative stress.

Lithostatic pressure may produce strain in rocks due to

simple compaction, but it probably cannot account for most

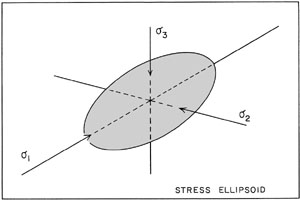

folding and faulting. For this, differential stress is required.

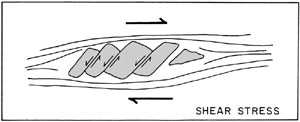

Differential stress may be developed by unequal normal stresses

or by shear stress—see Figs. 9-1 and 9-2.

| Figure 9-1. The stress ellipsoid: three normal (perpendicular) stress axes define the total stress applied to a rock body. õ1 is the maximum compressive stress, õ2 is the intermediate, and õ3 is the minimum. Normally, all three stresses are compressive; however, õ3 may be negative (tensional) in some cases. Where only lithostatic pressure is developed, the stresses are equal and the stress ellipsoid becomes a sphere.

|

| Figure 9-2. Hard augen, such as feldspar, within a ductile schist subjected to shear stress parallel to foliation. The sense of shear on oblique microfractures of augen is opposite to overall sense of shear in the rock. T symbolizes shear stress. Adapted from Simpson and Schmid (1983, fig. 9).

|

Strain in rocks is accomplished by dilation, which is a

change only in size, or by distortion, which is a pure shape

change, or commonly by both. Strain is most easily measured as a

percentage length change.

change in length

e = ---------------- x 100, where e = percent strain.

original length

The amount of strain is, of course, related to the magnitude

of stress, and the strain response of various rocks to stress may

be tested in laboratory apparatus. Prepared rock cores are

squeezed in a hydraulic press subjecting the rock to high õ1

compression. Measuring devices attached to the press and rock sample monitor pressure and detect minute strains in the rock. Pressures as high as 100 kb could be produced by uniaxial or triaxial hydraulic presses. The highest experimental compression yet achieved is produced by a diamond-anvil technique that has reached pressures of 1700 kb (Jayaraman 1984).

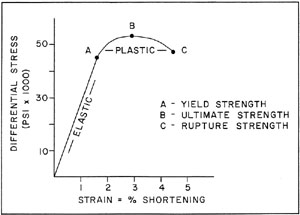

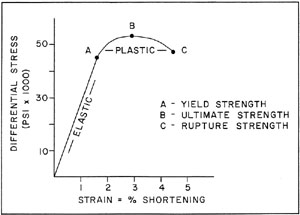

The standard means of portraying the behavior of a stressed

rock is with a stress-strain diagram, where strain is plotted on

the horizontal axis and stress is plotted on the vertical axis—see

Fig. 9-3. Strain is the percentage of shortening parallel to

õ1 and stress is the difference õ1 - õ3. As differential stress

increases, most rocks initially behave in an elastic manner. In other words, strain is directly proportional to stress, and strain disappears when stress is removed. This results in a straight line on the graph.

| Figure 9-3. Typical stress-strain diagram showing the behavior of a limestone subjected to increasing õ1 stress under a high confining pressure. Adapted from Davis (1984, fig. 5.25).

|

As differential stress is increased further, the rock

reaches the so-called yield strength or elastic limit, beyond which

the rock behaves in a plastic manner and the strain does not

disappear when stress is removed. Strain increases rapidly with

only slightly higher stress until the ultimate strength of the

rock is achieved. The rupture strength represents the point at

which the rock fails by fracturing. Under conditions of low

confining pressure, most rocks fail before reaching the elastic

limit, but the same rocks have a higher rupture strength and behave plastically under higher confining pressure, for instance under metamorphic conditions.

Rock failure

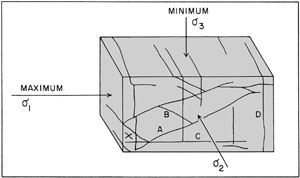

The failure of a rock by rupturing results in characteristic sets of fractures whose orientations are related to the õ1, õ2, and õ3 stress axes—see Fig. 9-4.

| Figure 9-4. Fractures produced experimentally in a block of Solenhofen limestone under differential stress. Fracture sets A and B are conjugate shear fractures, C are extension fractures, and D are release fractures. Adapted from Hobbs et al. (1976, fig. 7.31).

|

- Shear fractures – plane of failure oriented about 30° from õ1, 60° from õ3, and parallel to õ2. Most common type of fractures; two crossing sets may form.

- Extension fractures – plane of failure parallel to õ1 and

õ2, and perpendicular to õ3. Not common geologically;

develop only where there is little or no confining pressure.

- Release fractures – plane of failure perpendicular to õ1,

and parallel to õ2 and õ3. Develop when stress load is

released, as when deeply buried rocks are unloaded by erosion of overburden or removal of an ice sheet.

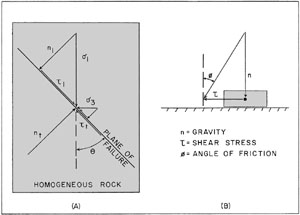

Shear fractures are the most common type of geologic fracture, and they develop because of the stress difference between õ1 and õ3. As õ2 is an intermediate stress, it may be ignored and shear fracturing analyzed in two dimensions—see Fig. 9-5A. Consider a plane within the rock which forms an angle (Ð) with the õ1 axis. The õ1 stress operating on the plane is composed of two components: (1) n1, a normal stress at right-angle to the plane, and (2) T1, a shear stress parallel to the plane. Likewise, the normal and shear stress components of õ3 may be determined and added to n1 and T1 to give the total normal stress (nt) and shear stress (Tt) operating on the plane. It is possible to calculate the total normal and shear stresses for a plane of any orientation using the following formulas.

õ1 + õ3 õ1 - õ3

n = ------- - ------- (cos 2Ð)

2 2

õ1 - õ3

T = ------- (sin 2Ð)

2

Where õ1 > õ3, shear stress is developed on all planes except those oriented Ð = 0° or 90°, and maximum shear stress is achieved on the plane at Ð = 45°. As rock shear strength is generally much less than compressive strength, shear fractures tend to develop obliquely to the õ1 axis during differential compression.

| Figure 9-5. A - components of normal (n) and shear (T) stresses affecting a plane of potential failure within a rock. Ð is the angle between the maximum stress and the plane of failure. B - normal stress (gravity), shear stress (T), and angle of friction (ø) for a brick being dragged over a horizontal surface.

|

Rocks subjected to differential compression develop maximum shear stress along planes oriented Ð = 45°. However, Figure 9-4 shows, actual shear fractures typically form at Ð = 30° to 35°. Shear fractures represent the initiation of faulting, and there are two attributes of rocks which resist faulting--cohesive strength and internal friction. Both of these phenomena are demonstrated by dragging a brick over a horizontal surface—see Fig. 9-5B.

In order to drag the brick, a horizontal shear stress must

be applied. The total stress operating on the brick is the shear

stress plus the normal stress of gravity, and the total stress

vector forms an angle (ø) with the vertical. This represents the

angle of internal friction; its magnitude is a measure of frictional resistance to sliding of the brick. Now, suppose the brick is bonded to the underlying surface by mortar. An additional shear stress must be applied to break the bond before any movement could take place. This additional shear stress, labelled To, is the cohesive strength of the mortar.

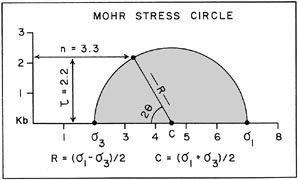

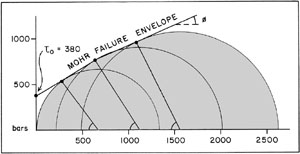

Mohr diagram

The Mohr stress circle provides a convenient graphical

means of solving the normal and shear stress equations presented

in the previous section. Normal stresses are plotted on the

horizontal axis and shear stress read on the vertical axis—see Fig.

9-6. A semicircle with its center on the normal stress axis at

(õ1 + õ3)/2 connects õ1 and õ3, and the radius of the semicircle equals (õ1 - õ3)/2. The angle 2Ð is measured from õ3 in clockwise direction.

| Figure 9-6. Basic Mohr diagram showing normal stress (horizontal axis) and shear stress (vertical axis) developed on a plane at Ð = 30° (2Ð = 60°) with õ1 = 7 kb and õ3 = 2 kb. Solving the stress equations for this situation gives n = 3.25 kb and T = 2.17 kb.

|

The point on the semicircle for a given 2Ð angle indicates a

normal stress value and a shear stress value for a plane oriented

at angle Ð within a rock. The maximum shear stress is achieved at

the top of the circle, where 2Ð = 90°, or Ð = 45°.

Thus, the maximum shear stress is equal to the radius of the Mohr

stress circle. Note that the Mohr circle has no physical reality;

it is simply a graphical solution to the stress equations.

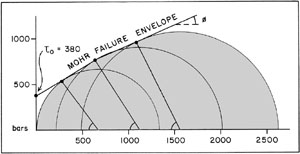

A series of stress circles representing different test conditions for a particular rock may be plotted together to produce a Mohr failure envelope—see Fig.9-7. Each Mohr circle represents the õ1 and Ð conditions of shear fracturing for a given confining pressure (õ3). As confining pressure increases, the õ1 stress and Ð angle at which failure occurs also increase. The points of rock failure on each circle define a line that is more-or-less straight at lower confining pressures and flattens out toward higher confining pressures. This line is the failure envelope; its intercept with the shear-stress axis gives cohesive strength (To), and its slope is the angle of internal friction (ø). Any point on or above the failure envelope represents stress conditions that would cause the rock to fracture.

| Figure 9-7. Mohr failure envelope for Carrara Marble. To represents cohesive strength, and ø is the angle of internal friction.

|

Construction of a Mohr failure envelope represents a

powerful means of evaluating rock strength, and a great many

failure envelopes have been determined for all kinds of rocks

under various temperature and pore-fluid conditions. The angle

of friction and cohesive strength vary widely—see Table 9-1. Based

on the geometry of the failure envelope, it may be seen that ø is

related to 2Ð, such that:

- ø = 90 - 2Ð, or Ð = (90 - ø)/2.

As many rocks possess an internal angle of friction of

approximately 30°, the Ð angle of shear fractures is

typically also about 30°.

Table 9-1. Average values for angle of friction (ø) and cohesive strength (To in bars) in various rock types.

| Rock Type | ø | To |

| Igneous: Plutonic | 45.6 | 561 |

| Igneous: Volcanic | 24.7 | 322 |

| Metamorphic: Foliated | 27.3 | 457 |

| Metamorphic: Non-foliated | 36.6 | 229 |

| Sedimentary: Clastic | 29.2 | 317 |

| Sedimentary: Chemical | 35.9 | 263 |

| All Types (average) | 32.0 | 345

|

Based on Kulhawy (1975, table XI).

Problem

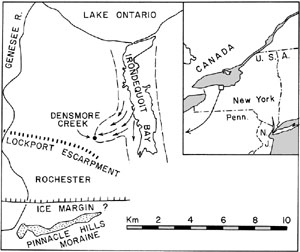

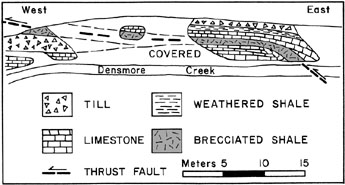

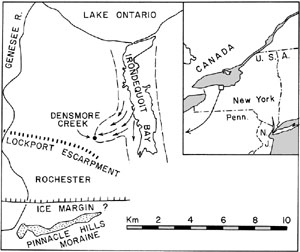

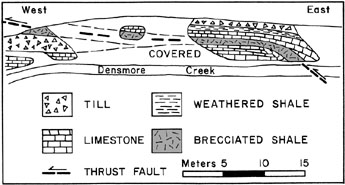

Andrews (1980) has described glacial thrusting of Paleozoic limestone and shale along Densmore Creek in western New York near Rochester—see Fig. 9-8. A bedrock mass consisting of limestone and weathered shale has been thrust along a zone of brecciated shale containing disoriented angular blocks of limestone—see Fig. 9-9. Below this thrust, till rests on intact Irondequoit Limestone at the western end of the section, and overturned folds are developed in the limestone at the eastern end of the section.

| Figure 9-8. Map of Densmore Creek and vicinity showing local ice movement (arrows) along bedrock valley (dashed line) of Irondequoit Bay. Based on Andrews (1980, figs. 1 and 6).

|

| Figure 9-9. Densmore Creek section showing thrust bedrock mass. Thrust zone is located within a brecciated shale unit. Based on Andrews (1980, fig. 2).

|

| Genesse River gorge in western New York, near Rochester. Known as the Grand Canyon of the East, a thick sequence of upper Devonian clastic strata is exposed in the walls of the gorge. |

The orientations of these folds and nearby striations indicate that ice flow locally turned toward the southwest following a bedrock valley tributary to Irondequoit Bay. The ice margin at

the time of thrusting was probably only a few km to the south, so

that ice thickness at the site of thrusting was likely no more

than 300 m.

A temperate glacier, which is separated from its bed by a

film of meltwater, may develop basal shear stress up to 1 bar,

and basal shear stress may reach 10 bars for glaciers frozen to

the substratum (Weertman 1961). The lithostatic pressure developed at the base of a glacier is given by:

lithostatic P (in kg/cm²) = ice thickness (in m) x 0.09

- Intact sample-cores of the Irondequoit Limestone have an

average unconfined compressive strength of approximately

1200 bars. Construct a Mohr stress circle for the Irondequoit Limestone.

- Assume an average ø value of 36° for limestone (chemical sedimentary rock), and plot a straight-line failure envelope on the Mohr diagram. Determine the To and

Ð values.

- Use the stress equations to calculate T and n stress values

for unconfined failure of the Irondequoit Limestone. Compare calculated values with graphical results.

- Assume the glacier was 300 m thick over Densmore Creek when

bedrock thrusting took place. Calculate the confining

(lithostatic) pressure developed at the base of the ice.

- Plot the basal stress conditions for both frozen and thawed

glacier-bed situations on the Mohr diagram. Are the stresses developed for either type of glacier bed sufficient to fracture intact Irondequoit Limestone?

- Based on your answer to question 5 and the geological

setting (fig. 9-9), explain how ice shoving was able to

thrust bedrock at Densmore Creek.

References

- Andrews, D.E. 1980. Glacially thrust bed-rock--An indication of late Wisconsin climate in western New York State. Geology 8, p. 97-101.

- Davis, G.H. 1984. Structural Geology of Rocks and Regions. J. Wiley & Sons, New York.

- Hobbs, B.E., Means, W.D. and Williams, P.F. 1976. An Outline of Structural Geology. J. Wiley & Sons, New York, 571 p.

- Jayaraman, A. 1984. The diamond-anvil high-pressure cell. Scientific American 250/4, p. 54-62.

- Kulhawy, F.H. 1975. Stress deformation properties of rock and rock discontinuities. Engineering Geology 9, p. 327-350.

- Simpson, C. and Schmid, S.M. 1983. An evaluation of criteria to deduce the sense of movement in sheared rocks. Geological Society of America, Bulletin 94, p. 1281-1288.

- Weertman, J. 1961. Mechanism for the formation of inner moraines found near the edge of cold ice caps and ice sheets. Journal of Glaciology 3, p. 965-978.

Return to Table of Contents.

Notice: This course was prepared for the use and benefit of students enrolled at Emporia State University. Others are welcome to view the course webpages. Any other use of text, imagery or curriculum materials is prohibited without permission. © J.S. Aber (2021).

Return to Table of Contents.

Notice: This course was prepared for the use and benefit of students enrolled at Emporia State University. Others are welcome to view the course webpages. Any other use of text, imagery or curriculum materials is prohibited without permission. © J.S. Aber (2021).

![]() Return to Table of Contents.

Return to Table of Contents.