|

History of Geology |

Born: Niels Stensen, 11 Jan. 1638, Copenhagen, Denmark.

Died: 5 Dec. 1686, Schwerin, Germany.

| Introduction | Major work |

| Later life | Historical assessment |

| Steno and Denmark | Reference and related |

|

History of Geology |

Born: Niels Stensen, 11 Jan. 1638, Copenhagen, Denmark.

Died: 5 Dec. 1686, Schwerin, Germany.

| Introduction | Major work |

| Later life | Historical assessment |

| Steno and Denmark | Reference and related |

Steno converted to Catholicism in 1667, and he returned to Denmark for a few years. His last significant scientific effort was his Prooemian lecture in Copenhagen in 1673, in which he presented a modern philosophy of science. As a Catholic in Lutheran Denmark, he was not happy, and moved back to Florence, where he became a priest in 1675. In 1677 he was appointed titular Bishop and spent the rest of his life involved with missionary work in northern Germany. He was given saintly status by Pope John Paul II in 1988. It is likely that Steno was one of the last successful polymaths.

Steno developed an exceptionally advanced concept of muscle function, one that was largely ignored or considered misleading until it was vindicated in the 1990s (Hansen 2009). Thus, Steno had achieved anatomical fame already before the age of 25. He sought a university position in Copenhagen, but was turned down. At that time, faculty positions went to relatives of the head professor. Thus, this famous native son was rejected in his own country. After a time in France, he travelled in Austria and Hungary.

In 1666 (or 1665) he became physician to the Grand Duke in Florence, Tuscany (Italy). Ferdinand II of Medici was wealthy

and gave Steno considerable freedom. His first contact with geology came at this time (1666), when he dissected the head of an unusually large shark.

As a Catholic, he was uncomfortable in a Lutheran country. So he left again. He became tutor to the son of Grand Duke Cosmo III in Florence, and devoted himself increasingly to religious matters. Steno became a priest in 1675, and in 1677 he was appointed titular Bishop of Titiopolis, a no-longer-existing city in the fallen East Roman Empire. In fact, he became the chief of Catholic missionary work in northern Germany. He was so consumed by this work that his health deteriorated, and he died at age 48. Steno's body was moved in 1953 into a marble sarcophagus in a chapel of the San Lorenzo Cathedral, Florence (Hansen 2009), and Steno was given saintly status by Pope John Paul II in 1988.

Nonetheless, the Prodromus was immediately translated into English by Henry Oldenburg, but Robert Hooke accused Oldenburg of stealing his ideas and giving credit to Steno. This put a damper on the Prodromus in England. Most other Latin works by Steno, however, were not translated until the twentieth century. For example, Prooemian was not translated into English until 1994 (Hansen 2009).

More important factors were nationality and religion. Steno was born and raised as Lutheran in Denmark, a relatively small country, which had suffered declining fortunes during the Little Ice Age. While other western European countries had acquired massive New World empires, Denmark's colonies included Greenland, Iceland, and the Faeroe Islands, legacies of a long-gone Viking Age. Steno's advanced studies and scientific works took place in larger, richer countries, particularly Italy, France, and the Netherlands. However, the national pride which has brought many names of less brillant scientists to greater fame did not apply to Steno (Hansen 2009, p. 21).

Steno's religious conversion also played a prominent, perhaps most important, role for his scientific disappearance. Conversions from Protestantism to Catholicism were widespread during the counterreformations of the seventeenth century. Steno was suspect from both points of the religious divide. In Protestant northern Europe, reference to Steno was dangerous; whereas in Catholic southern Europe, Steno was considered somewhat dubious (Hansen 2009).

Alexander von Humboldt rediscovered the Prodromus in 1823, and notified Charles Lyell (England) and Elie de Beaumont, who founded the first geological survey of France (Hansen 2009). Subsequently many other influential geologists came to rely on Steno as an authority. Steno's revival continued during the nineteenth century, and at the Second International Geological Congress in 1881, he was proclaimed the Founder of Geology.

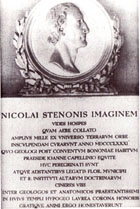

Woodcut illustration of Nicolaus Steno.

Return to history of geology syllabus or schedule.Introduction

Niels Stensen (also Nils or Steensen) was born to a wealthy family of Lutheran goldsmiths in Copenhagen. His name means literally Niels, "Son of Rocky" (sten = stone or rock). He studied medicine first in Copenhagen then in the Netherlands at Leiden and Amsterdam.

Commemorative plaque, Klareboderne, Copenhagen. The plaque states: Here was born Niels Stensen, 1638 to 1686; anatomist, geologist, bishop (JSA translation). The heart with a cross is highly symbolic. A symmetrical heart and cross had been used previously in his family and still appears in southern Ireland today. The asymmetric heart alludes to Steno's anatomical investigation of the heart as a muscle (Hansen 2009). Image obtained from Wikimedia Commons.

Steno's sketch of the shark head and teeth (1667).

Image obtained and adapted from Wikimedia Commons.

Major work

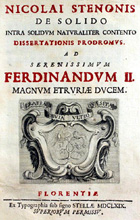

Steno then began intensive geological study and travel in Tuscany. He visited quarries, mines, and caves; he saw the famous Carrara Marble, Appenine Mountains, Arno River, and coastal lowlands. In the midst of this, he was converted to Catholicism in 1667. He also received requests from the Danish King to return to Copenhagen. He knew he could not resist the king for long, so in 1668 he wrote his most important work, one which is now regarded as a classical geological masterpiece—De Solido Intra Solidium Naturaliter Contento Dissertationis Prodromus (Forerunner of a dissertation of a solid naturally contained within a solid),

often now called simply the Prodromus.

Title page from Steno's De Solido ... Prodromus (1669).

Image obtained and adapted from Wikimedia Commons.

The preservation criterion is one that has faced geologists every since, namely the rock record is an incomplete account of earth history. Crucial information is missing for certain places and intervals of time. Regarding the chronology criteria, Steno formulated five principles known as Steno's laws of stratigraphy (Hansen 2009).

These laws are the foundation of modern geology and paleontology. The law of intersection, for example, resembles Hutton's later well-known unconformity concept. Fossils are anatomically identical with parts of living organisms, particularly teeth, bones, and shells. Fossilization into crystalline material takes place over long passage of time; thus, many fossils must be as old as the general deluge. Steno interpreted all rocks in terms of deposition of sediment from fluid. He apparently knew nothing of granite or lava, which are not in Tuscany. He made few (if any) geological observations outside of Tuscany.

Portrait of Steno. Unsigned but probably painted between 1666 and 1677 by Justus Sustermans.

Part of a series of portraits of people who were associated with the Court of Ferdinand II and Cosimo III.

Image obtained and adapted from Wikimedia Commons.

Catholic censors had to approve all scientific publications in Steno's time. The first censor, Viviani, was sympathetic and approved; however, the second censor delayed four months before approval. The publication in 1669 ultimately was arranged entirely by Viviani.

Later life

Steno returned to Denmark, where he was professor of anatomy at the University of Copenhagen (1672-74). His last significant scientific effort was his Prooemian (prologue) lecture in Copenhagen in 1673. This lecture drew on many of his anatomical and geological findings and is regarded as one of the clearest formulated philosophies of modern science as it appeared during the 17th century (Hansen 2009, p. 1).

Portrait of Steno in clerical garb (J.P. Trap 1868).

Image obtained from Wikimedia Commons.

Historical assessment

During Steno's lifetime, his anatomical and geological works were highly regarded by many contemporaries. Following his death, however, Steno was largely forgotten or ignored from about 1700 to around 1830. Part of the explanation for this has to do with languages. All of his writing was in Latin (except one in French). His Latin had great beauty and poetic value, which made translation into other languages a daunting task.

Nicolaus Steno memorial leaf, Florence. Dedicated by

the Second International Geological Congress in 1881.

Image obtained from Wikimedia Commons.

Steno and Denmark

Danish geologists today are proud to claim Steno as a native son, in spite of the ironic facts that he was twice forced to leave his homeland and that he never practiced geology in Denmark. Furthermore, the official state Church of Denmark (Den Danske Folkekirke) is an Evangelical Lutheran Church, and the country is overwhelmingly Protestant. Steno is commemorated by the Steno Geology Student Club at the University of Copenhagen.

Taken from the Steno Songbook

(Steno geology student club, 1973).

Reference

Related websites

Related websites

© J.S. Aber (2017).