| Chamberlin

History of Geology |

Born: Sept. 25, 1843, Mattoon, Illinois.

Died: Nov. 15, 1928 in Chicago.

| Abstract | Introduction |

| Glacial geology | Later career |

| Chamberlin & Gilbert | References |

| Chamberlin

History of Geology |

Born: Sept. 25, 1843, Mattoon, Illinois.

Died: Nov. 15, 1928 in Chicago.

| Abstract | Introduction |

| Glacial geology | Later career |

| Chamberlin & Gilbert | References |

Chamberlin's career followed one overriding interest—glacial geology. Work with the Wisconsin Geological Survey and the USGS in the 1870-80s resulted in accurate mapping of the limits of glaciation in the United States, in basic laws of glacier ice movement, and in recognition of multiple glaciations. These results are contained in two classic monographs of the USGS: Preliminary paper on the terminal moraine of the second glacial epoch (1882) and The rock scorings of the great ice invasions (1886). Chamberlin developed the terminology for glacial stages in North America that is still utilized with some modifications.

His later interest expanded to consideration of the causes of glaciation and climatic change and ultimately to the origin of the Earth. He devised the "planetesimal theory" for the origin of the Earth, which contrasted with the more-popular nebular-gas-cloud theory. Chamberlin coauthored with Salisbury a widely used, three-volume college textbook, Geology (1906). A generation of geologists were trained with this text, and Chamberlin was highly regarded by contemporary and later geologists.

Chamberlin was born on a glacial moraine in Illinois, and the family moved to Beloit,

Wisconsin at age three. This was the prairie frontier region in the 1840s. His father

was an abolitionist and sometime preacher. Chamberlin graduated from Beloit College in

1866, where he had a classical education in Greek and Latin. He spent the next two years

as a high school principal in Wisconsin. In 1868-69, he took graduate courses, including

geology, at the University of Michigan. He was appointed professor of natural sciences

at the State Normal School (Wisconsin), 1869-73, and from 1873-82 he was professor of

geology at Beloit College. Meanwhile, he cofounded the Wisconsin Academy of Sciences in

1870.

Chamberlin explored the scientific process itself. He developed the method of "multiple

working hypotheses," which became the standard approach for several decades. It is still

widely utilized, but has been displaced by the "model-building method" in recent years.

Chamberlin saw two fundamental modes for investigation of the Earth.

Return to history of geology syllabus or schedule.Introduction

Chamberlin was a glacial geologist and science educator, who supported the concepts of

multiple glaciation and planetesimal origin of the Earth. He was the founding editor

of the Journal of Geology at the Department of Geology, University of Chicago.

Chamberlin was an unusually successful blend of field geologist, government bureaucrat,

university teacher and administrator, and cosmic theorist.Glacial geology

At the Wisconin Geological Survey, Chamberlin was the assistant state geologist (1873-76),

and he was promoted to Chief Geologist (1876-82), while still teaching at Beloit College.

In a 4-volume set on geology of Wisconsin, he introduced the concept of multiple (2) glacial

periods during the Ice Age (Quaternary Period), based on study of glacial moraines in

eastern Wisconsin. In 1881 he entered the U.S. Geological Survey, while still holding his

other appointments. He was placed in charge of the glacial division, where he remained until

1904. In 1882-87 he resided in Washington, D.C., and he taught at George Washington University

(1885-87). During this time, he was associated with many other well-known glacial geologists,

including J.E. Todd and L.C. Wooster who later worked in Kansas (Aber 1984).

Portrait of Thomas Chrowder Chamberlin in the 1870s. In the public domain; obtained from Wikimedia Commons.

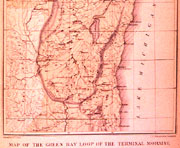

Chamberlin's map of moraines in Wisconsin. This map was the first

demonstration of fundamental laws of glacier ice flow in lobate fashion. Taken from

Chamberlin (1882, plate XXIX). Later career of Chamberlin

Chamberlin served as President of the University of Wisconsin from 1887 til 1892. He

modernized the university from a classical emphasis to a scientific emphasis, a difficult

job for which he proved quite capable. In 1892, he accepted the Chair of the new Department

of Geology, University of Chicago. The U. of C. was founded and funded by J.D. Rockefellar

on the old World's Fairground. Thus, Chamberlin stepped down from full-time administrative

responsibilities in order to devote more time to geology. He assembled a hand-picked faculty,

including R.A.F. Penrose, Jr. Chamberlin founded and was first editor of the Journal of

Geology, which was established as a departmental journal in 1893. It was a convenient

forum for publication of his ideas in glacial stratigraphy. The Journal of Geology

became one of the leading geological journals, a status it continues to maintain today.

Portrait of Thomas Chrowder Chamberlin in 1897. In the public domain; obtained from Wikimedia Commons.

Chamberlin's (1896) classification for North American

Chamberlin's (1896) classification for North American

glacial stages with subsequent modifications.

Glacial Stage

Interglacial

Modification Relative

Age

Wisconsin In current use

Toronto Replaced by Sangamon

Iowan (deleted)

interglacial (deleted)

Illinoian In current use

interglacial Now Yarmouth

Kansan Replaced by Independence

Aftonian (obsolete)

Albertan (obsolete)

Chamberlin retired from active duty at the University of Chicago and became professor

emeritus in 1919. He remained quite productive, nonetheless, until his death in 1928. Chamberlin was

highly regarded by his own and following generations. His scientific ideas and text

books were highly influential. A whole issue of Journal of Geology was devoted to him

in 1929, and a GSA symposium was held in 1989.

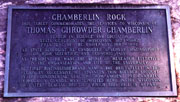

Memorial plaque for T.C. Chamberlin at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. Photo © J.S. Aber.

Chamberlin and Gilbert

Chamberlin and Gilbert had much in common during their early careers. Both were exceptional

field geologists, and both introduced important new concepts based on field investigations.

They were well acquainted with each other and maintained a friendly relationship. However,

their later careers show a divergence. Gilbert disliked administrative and bureaucratic

affairs, and he refused to teach. He remained a solitary field geologist to the end. In

contrast, Chamberlin enthusiastically took on ever greater teaching and administrative

burdens. Chamberlin's fame as an educator is equal to his stature as a geologist. In this

regard, Chamberlin had greater long-term impact on geology than did Gilbert.References

© J.S. Aber (2017).