| Wetlands of Southern

Saskatchewan, Canada

James S. and Susan W. Aber |

Introduction

We have visited the Canadian Prairie provinces several times in the past, and we decided to take kite aerial photography into southern Saskatchewan, where we visited colleagues and friends in Regina in July 2010. Our primary objective was to observe and photograph wetlands of the prairie pothole region, which includes the formerly glaciated portions of the north-central United States and southern parts of Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta (Dugan 2005), totaling 300,000 square miles (~780,000 km˛).

When the last ice sheet melted away from this region, some 15,000 to 12,000 years ago, the landscape was left with millions of large and small poorly drained depressions that became marshes, wet meadows, ponds, and shallow lakes. The emergent and shallow-water zones are highly productive; cattail and bulrush are the primary emergent plants along with many other types of aquatic vegetation (Lahring 2003).

|

| Representative vegetation in wetlands of southern Saskatchewan. Left: cattail behind with floating mats of pondweed. Middle: cluster of bulrush. Right: close-up view of pondweed. |

Ducks and wetlands go together, and this region is famous for its duck and goose populations. Half of all North American waterfowl spends the summer in the prairie potholes, where many species of dabbling and diving ducks breed, feed, raise young, and prepare for fall migrations southward. Niering (1985) stated that the prairie pothole region can support up to 140 ducks per square mile (2.6 km˛).

|

| Pair of ruddy ducks (Oxyura jamaicensis)—female left, male right—on a marshy pond near Redfox Lake. These diving ducks seldom fly. They escape from danger by slowly sinking out of sight or hiding in marsh vegetation (Niering 1985). |

It is no surprise that this rich biological resource has attracted much attention from hunters, birdwatchers, and others who seek to protect and maintain natural environments. Several national and provincial agencies are involved as well as many non-governmental organizations, most importantly Ducks Unlimited Canada. Our KAP sites ranged from small potholes with little or no human impact to large wetlands that are heavily manipulated. The summer of 2010 was unusually cool with frequent rain, which certainly benefited the wetlands.

|

| Southern Saskatchewan showing four localities where we conducted kite aerial photography. 1 - Dirt Hills, 2 - Lake Oro, 3 - Old Wives Lake, and 4 - Luck Lake. Map obtained and modified from the Atlas of Canada. |

| During our week in Saskatchewan wind varied considerably. At some sites, we utilized a small delta with a tail to handle relatively strong and gusty winds (15-25 mph). For moderate breeze, our yin-yang Daruma rokkuku (left) proved most suitable. This kite measures ~5x6 feet and flies well in 10-20 mph wind. We flew it sometimes with a tail, sometimes without. Cameras included the Canon SD600, S70, and R1000 models—see cameras.

|

Dirt Hills

The Dirt Hills are a series of bedrock ridges thrust up by glacial movement along the margin of the Missouri Coteau. The Dirt Hills are impressive topographic features that stand up to 1000 feet (300 m) above the lowland to the north. They are among the largest ice-shoved ridges in the world (Aber and Ber 2007). The lower flanks of the hills are cleared for agricultural fields, but the steeper crest of the hills remains in prairie for cattle grazing. Between individual ridges, swales contain numerous small lakes, marshes and wet meadows. We conducted KAP at two abandoned farmsteads, about two miles apart, in the northeastern portion of the Dirt Hills.

| Our first KAP site in the Dirt Hills next to an abandoned farmstead (left) and a small marsh (right). The marsh is almost completely filled in with a mosaic of cattail (a) and bulrush (b); only a small area of open water remains on the far side of the township road. |

| View northward from the first site. The crest of the Dirt Hills shows on the horizon. The yellowish-green crop field in the middle distance is canola (see next picture). |

| Looking to the northeast from the second Dirt Hills site. The canola field in previous picture is visible in far left distance. Pond at bottom of view was our main subject at the second site. |

| Marshy pond at second Dirt Hills site. Left - superwide-angle overview. Right - close-up, near-vertical view. Bulrush surrounds the marsh, and algae cover most of the pond. Notice dark reddish-brown color of water at pond center. This is probably a result of bacterial growth.

|

|

Lake Oro

Lake Oro occupies a deep kettle hole. This depression formed when glacial meltwater floods buried a stagnant block of ice in sand and gravel. Later, when the ice melted, a pronounced depression was left in the outwash plain. Lake Oro is today a small provincial park. We arrived in late afternoon and set up as a thunderstorm began to move in from the northwest. Once kite and camera were in the air, we realized the storm was building faster than we had expected. We quickly took a few pictures, brought down the camera and kite, and departed before the storm arrived.

| Superwide-angle overview looking toward the south with Lake Oro on the left. Kite flyers are standing on the right bluff above the lake basin.

|

Old Wives Lake

| Old Wives Lake is a large, shallow, saline lake. It originated during the last phase of glaciation as a proglacial lake that was dammed between the edge of the ice sheet to the north and higher ground to the south. The proglacial lake filled and overflowed into a spillway valley now occupied by Lake of the Rivers to the south. When the ice sheet retreated, the lake shrank into its present broad, enclosed basin, which is fed from the west by Wood River.

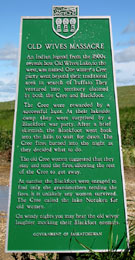

Old Wives Lake was designated as a Migratory Bird Sanctuary in 1925; it covers more than 26,000 hectares (65,000 acres). It also is listed as a Ramsar Wetland of International Importance. Its name derives from an Indian legend (see historical sign). |

Old Wives Lake is the fourth largest saline lake in North America. Given its great surface area and shallow depth, it is subject to large changes in size from year to year during drought and flood cycles. Sodium sulfate is present both in the brine and in salt deposits, mainly as the mineral mirabilite (Glauber's salt), which was produced commercially in the past from the southeastern end of the lake.

As an historical note, Glauber’s salt was first recognized by a 17th century Dutch/German chemist and apothecary Johann Glauber. It was named sal mirabilis or the miracle salt because of its medicinal use as a laxative. Although mirabilite is still used as a laxative, primarily in Chinese medicine, greater uses for this sodium sulfate today are as filler in powdered home laundry detergents and carpet fresheners, as well as a fining agent in the glass industry and a cattle feed additive.

| Left: kite flyers are set up on a little-used township road near the southeastern end of Old Wives Lake. Lake basin to right and foreground; agricultural fields in the background. Right: view toward the east over the southeastern margin of Old Wives Lake, which is mostly a mud/salt flat in this portion.

|  |

| Water pool toward the center of Old Wives Lake. Left: view northward with cloud reflections from the water surface. Right: looking toward the northwest; a high shoreline is marked by a sinuous line of brush across the left side and right foreground.

|  |

Luck Lake

| Luck Lake is a Saskatchewan Heritage Marsh that includes 6170 acres (~2470 ha) of wetland and 650 acres (260 ha) of adjacent upland. The lake is the terminal point of a small enclosed drainage basin. Water-control structures were built in 1988 by Ducks Unlimited Canada, which continues to manage the lake.

|

In addition to the partners noted above, the Birsay Water Users Association, Saskatchewan Water Corporation, Rural Municipality of Coteau, local landowners, and federal government were instrumental in organizing the project. Water for Luck Lake comes from nearby Lake Diefenbaker, a huge reservoir on the South Saskatchewan River (see map above), via high-pressure pipeline that supplies irrigation to local farmers. We conducted KAP from two sites—first on the eastern end of the lake and then from the southern side—near to where pipelines bring water to the lake.

East end Luck Lake

| Overviews of Luck Lake. Left: looking toward the southwest. The second KAP site on southern side is marked with asterisk (*). Right: looking toward the northwest. Notice pools with distinctly different water conditions.

|  |

| Adjacent agricultural land. Left: view toward north with eastern end of Luck Lake on left and farms on right. Right: center-pivot irrigation for a field of canola. The ditch in foreground carries water into Luck Lake from a pipeline east of the lake.

|  |

| Water control. Left: close-up shot of kite flyers on a narrow dike that separates pools with quite different types of water. Water from the deep pool on right drains through the culvert into the main marsh on the left. Right: culvert that drains from the storage pool behind into the main marsh.

|

|

South side Luck Lake

| Overviews of Luck Lake. Left: looking toward the northwest showing a dike that angles across the lake. Right: scene toward the northeast reveals distinct multi-colored bands of emergent vegetation along the shore.

|  |

| Close-up aerial views. Left: vegetation zones on the southern side of Luck Lake. The maroon-colored plant is red samphire, and the straw-white plant is foxtail barley. Right: pipeline water supply comes into the fenced rectangle (left side) and flows into the western side of Luck Lake. Kite flyers are next to near corner of the pipeline rectangle at this public viewing site.

|  |

| Ground shots of distinctive vegetation. Left: red samphire (Salacornia rubra), which grows on saline mud flats (comb is ~12 cm long). Right: foxtail barley (Hordeum jubatum), a long-awned foxtail commonly found on the margins of saline marshes (Lahring 2003).

|

|

Related sites

Related sites

- More about Old Wives Lake from the Encyclopedia of Saskatchewan.

- Saskatchewan Migratory Bird Sanctuaries—see MBS from Environment Canada.

- Ducks Unlimited Canada in Saskatchewan.

References

- Aber, J.S. and Ber, A. 2007. Glaciotectonism. Developments in Quaternary Geology 6, Elsevier, Amsterdam, 246 p.

- Dugan, P. (ed.) 2005. Guide to wetlands: An illustrated guide to the ecology and conservation of the world's wetlands. Firefly Books, Buffalo, New York, 304 p.

- Lahring, H. 2003. Water and wetland plants of the Prairie Provinces. Canadian Plains Research Center, Regina, Canada, 326 p.

- Niering, W.A. 1985. Wetlands: The Audubon Society Nature Guides. Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 638 p.

Acknowledgements: Thanks to David and Mary Sauchyn, Hans and Ingeborg Schlichtmann, and David Ackerman for logistical support and suggesting sites for us to visit during our stay in Saskatchewan.

Return to gallery or kaphome.

Return to gallery or kaphome.

Last update: July 2010.

![]() Related sites

Related sites![]() Return to gallery or kaphome.

Return to gallery or kaphome.